Deep Impact

Understanding the impact of complex trauma on spirit, soul and body

WHEN YOU THROW A STONE INTO A TRANQUIL POND, immediately the quiet balance of the water is disturbed. First there is the splash as the stone hits the water, the initial impact. But, as one watches, ever widening concentric ripples begin flowing out from the place of impact. The larger the stone, the greater the initial splash. The deeper the impact, the wider the ripples that are created. If the stone finds a shallow, sandy landing the impact is softened. However, if the stone continues to fall into deep waters, everything around is impacted. So it is with trauma. Trauma can be described as a kind of injury. From a psychological perspective, a trauma is an experience which leaves an individual with an emotional wound. It stands to reason that the greater and more intense the trauma, the more difficulty an individual will experience in recovery.

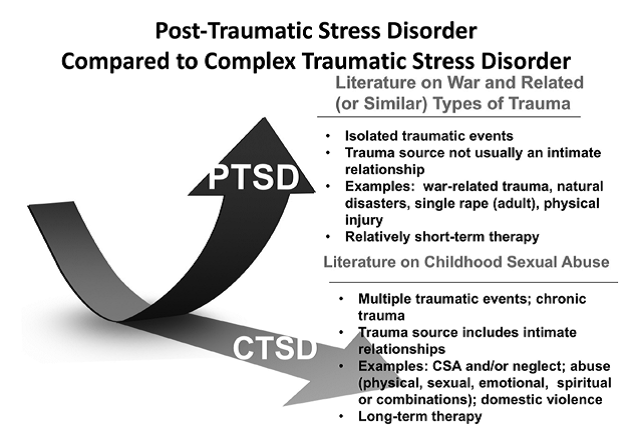

Let me give you an example. A soldier prepares for battle. He or she is conditioned through strenuous training for months, and given the tools necessary to go to war. They are assigned to a unit of comrades and sent off to war. They are prepared to fight, but not really prepared for the horror of war – how can one truly prepare for such a thing! This person may see a friend killed in front of them, or a child ignite a suicide bomb. Their psyche is deeply affected. How an individual deals with this profound emotional upheaval is important? If this person has deep inner resources and is able to talk to a trusted person about such horrors, the impact is lessened and they actually can go on to “fight another day.” For some this incident may cause acute traumatic stress, which lasts a maximum of 30 days. If this individual has experienced multiple incidents like this one, they could be susceptible to the condition of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Now let me give another scenario. A two-year-old child is repeatedly beaten by their father. At five years of age, the child is sexually abused by a relative, and over the next three years is continually beaten and sexually abused. The parents divorce and the abuse stops, but the damage is done. The child is left not only with the scars of abuse, but also with deep shame, anger, long-lasting grief and perhaps most profound – insecure attachment with caregivers. Such children frequently develop deep resources that help them cope with their pain – often by burying it so completely that even they cannot access the memories. As children they have learned how to perform, in order to ‘maintain’ a level of peace and it serves them well. Let’s say as an adult, this person joins the military. They have developed a deep resiliency to physical pain and often are viewed as high achievers and very self-disciplined. If nothing happens to upset this equilibrium all seems to goes along well. Then comes the trigger – perhaps it is like the one mentioned above; seeing innocent children wounded or killed. What may seem to others as a one-time event, is actually just the tip of the iceburg.

The emotional pain in both of these examples is deep, but the outcomes are often very different. Both of these individuals may experience suicidal ideation. The soldier (without pre-existing trauma) is more likely to fully recover – the general treatment for PTSD is usually completed in a twelve-week program.

If a soldier is repeatedly exposed to horror without the opportunity to process the emotional impact, they, too, can develop complex traumatic stress. The difference is that the first soldier has not experienced such intense childhood traumas, that has left him or her without secure attachment to family. They have most likely developed trust through a supportive family and close relationships, which helps them recover much quicker. This is something that the child of abuse was not able to accomplish.

The soldier who survived an abusive childhood might spend years in a never-ending cycle of depression and despair, frequented by unrelenting and often unidentified flashbacks, and nightmares stemming from their years of abuse. This condition is known as Complex Traumatic Stress Disorder. The individual may have sought counselling and seen a variety of therapists; sometimes being in therapy for several years with several different diagnoses before receiving the help they need for the underlying trauma.

The figure below indicates some of the differences between PTSD and CTSD.

(Gillies, 2016)

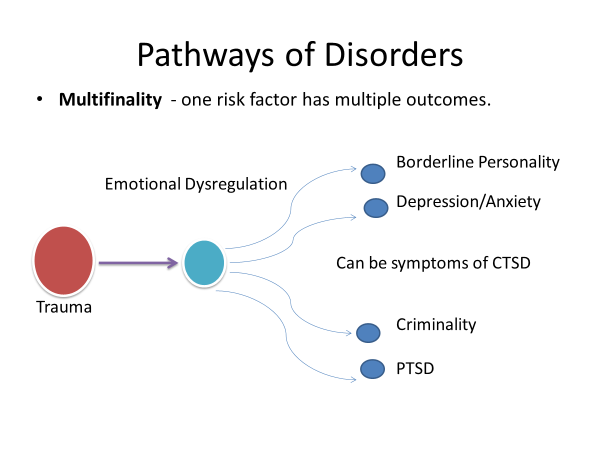

The following figure identifies how trauma (specifically habitual trauma, such as child abuse, torture, refugees, etc.) can lead to an emotional dysregulation causing a variety of diagnosis. What often happens is that the observable symptoms of the diagnosis are treated, but the underlying trauma lays unexposed.

In the immediate impact of a disaster the symptoms of Acute Traumatic Stress, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Traumatic Stress Disorder will look similar. This is the time where Critical Incident Stress Management procedures are most helpful.

Along with CISM I believe there is a need for those working with survivors of traumatic events – whether it be an act of terrorism or a catastrophic natural event – to be able to identify the symptoms of CTSD in order to be able to connect these individuals with the appropriate resources in the future. Symptoms of CTSD include the three core symptoms of PTSD: Re-experiencing; Avoidance; Hyper-arousal. Courtois & Ford (2009b) agree with other researchers regarding the wide range of symptoms, in terms of a number of intrinsically overlapping categories which include the following:

• Post-traumatic stress

• Cognitive disturbance – low self-esteem, self-blame, hopelessness, expectations of rejection and preoccupation with danger (eg.Briere, 2000a; Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin & Orsillo, 1999; Janoff-Bulman, 1992).

Chronically traumatized individuals will often have difficulties with affect regulation and may experience dissociation (the disconnection or separation of mind, will and emotion from the physical body). They will experience a distorted sense of self, low self-esteem and self-hatred, deep self-blame, high degrees of guilt and shame, severely impaired identity formation which can lead to identity confusion, severely impaired trust which interferes with the development of healthy relationships, resulting in disrupted attachment (Gillies, 2016).

In the next publication I will talk further about the implications of complex trauma on the spirit and soul.